- Microplastics have been discovered in human blood for the first time, in a new study of 22 people.

- It's the first evidence that human bodies are absorbing and circulating plastics through the bloodstream.

- The risks to human health are unclear, because research has focused on plastic additives.

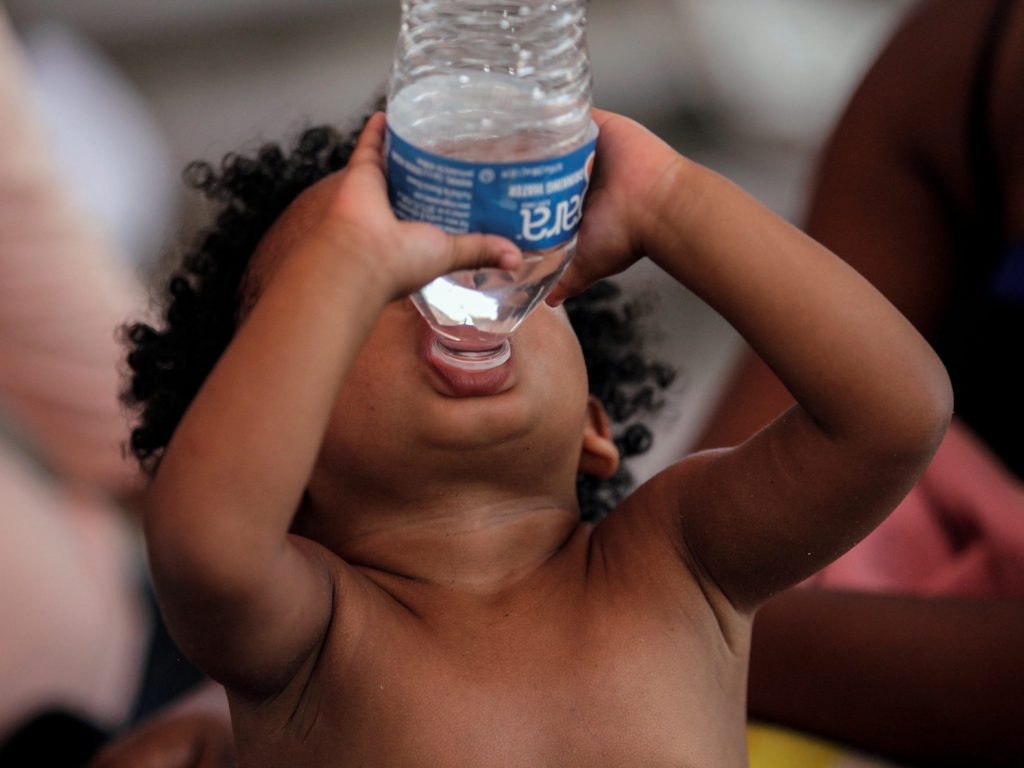

Microplastics — plastic fragments smaller than a fingernail that never fully break down — already seemed to be everywhere. They've been found in the Mariana Trench and at the top of Mount Everest, in dust and food and drinking water, in human placentas and baby bottles.

Now scientists have found them in human blood.

Of 22 healthy adults in a Dutch study, published Thursday in the journal Environment International, 17 had plastic particles in their blood. That's a small group of people, but the study is the first of its kind.

"This is really the first evidence of plastic polymers making it into the bloodstream," Rolf Halden, director of the Biodesign Center for Environmental Health Engineering at Arizona State University, who was not involved in the study, told Insider. "What that means is quite uncertain, but it is unsettling news."

Because it's in the food we eat, the water we drink, and the air we breathe, the average American ingests about 50,000 microplastic particles each year and inhales about the same amount, according to a 2019 analysis. Another study, from 2021, estimates that the average person ingests a credit card's worth of plastic each week.

Other research has discovered plastic in infant and adult poop, but that's just particles that pass through the digestive system without getting absorbed. Microplastics' presence in human placentas suggested that they were traveling through the blood, but it wasn't direct proof. This is the first definitive evidence of plastics absorbing into the human bloodstream, where they can travel all around the body, Halden said.

"That means that [microplastics] stick around longer than just going through the gastrointestinal tract," Heather Leslie, a chemist and ecotoxicologist, who led the study while working at Vrije Universiteit in Amsterdam, told Insider.

It's unclear what that means for human health. But by proving the presence of plastics in human blood, Leslie and her colleagues hope to garner more funding for research into potential health impacts.

"I expect in the end, we are all exposed," Marja Lamoree, a chemist at Vrije Universiteit who co-authored the study, told Insider.

"It's really too early to say whether it's safe or not," she added.

Scientists are 'in the dark' on plastic's health impacts

Studies on common chemicals in plastics have linked them to increased risk of cancer, fertility and development issues, and hormone disruption. However, most of the research on human health and plastics has investigated single molecules or additives like BPA, rather than the polymers — strings of molecules — that make up plastic itself.

When it comes to polymers in the blood, Halden said, "we are essentially mostly in the dark."

Leslie's team isolated the plastic particles from the blood, then heated the sample to vaporize any plastic additives present, so only the polymers remained.

These polymers are tiny residues of plastics that have crumbled into dust, which pervades our home environments, food, and water, and sheds from everyday items like clothing and tires.

"We've been using plastic for a century, but we haven't thought about the plastic dust until recently," Leslie said.

The next step was to further heat the samples in order to be able to measure the masses. Finally, they could calculate the mass of the polymers.

The study participants had an average of 1.6 micrograms of plastic polymers in every milliliter of blood. That concentration is equivalent to a teaspoon of plastic in 10 large bathtubs of water. It's both unclear what a safe concentration of blood plastic might be, and what the health impacts of too much plastic are.

There's plenty more plastic to study inside human bodies

Now that scientists know microplastics exist in human bloodstreams and can measure those plastics, they're aiming to learn more.

Leslie is part of a cohort of scientists expanding their research to examine more people's blood, she said. They're also testing gut and lung tissues for microplastics.

There are still smaller sizes of plastic particles that the new study couldn't measure. Those miniscule particles might be able to cross through the blood-brain barrier, or travel to other tissues, potentially wreaking havoc scientists haven't yet discovered.

"Plastics are everywhere," Halden said, adding, "And now we learn that it is not confined to the environment, but that it has entered us. And the outcomes of that exposure are, right now, unknown."